I recently visited Wesserling Park, a former royal factory and textile city in Alsace, specializing in Indian printed fabrics, or the production of Indian cotton. These sumptuous fabrics, woven and painted in India and block-printed with large, exotic, and richly colored floral motifs, enjoyed phenomenal success throughout Europe, particularly in France, from the 16th century onward.

History of Indiennes*

Indian printed fabrics: the cotton canvas revolution

*Indiennes (French: [ɛ̃.djɛn], lit. ’that which comes from Eastern India’), was a type of printed or painted textile manufactured in Europe between the 17th and the 19th centuries, inspired by similar textile originally made in India (hence the name). Indiennage: the making of Indian printed fabrics by Europeans.

The History of fabrics printing began in India. Indian artisans mastered techniques unknown to Europeans that allowed madder reds and indigo blues to be fixed to the canvas using metallic salts (alum was traditionally used). These cotton canvases were imported from the ‘Comptoirs des Indes’ to Europe at the end of the 16th century, and quickly won over all sections of the population with their lightness and ease of maintenance. Indeed, the vividness of their colors was as appealing as they were resistant to washing. In France, Madame de Pompadour (‘favorite’ of Louis XV) was crazy about Indian printed fabrics, as was the entire bourgeoisie.

In the 17th century, Armenian merchants copied Indian techniques to print cotton fabrics, particularly in Marseille (the Indians of Marseille). During the same period, factories developed in England and the Netherlands. Thus, alongside imported fabrics, a European production of Indians was born, printed in Europe, near ports and trade routes, from imported white cotton canvas.

Prohibition

The passion for these fabrics in France was such that the local silk, wool, and linen or hemp industries complained about them. Louvois, Louis XIV’s Minister of State, therefore prohibited the wearing, sale, and importation of Indian printed fabrics by an edict published on October 26, 1686, which expired in 1759. The importation of fabrics was only authorized on the condition of re-exporting them immediately, which was only partially done and fueled smuggling. Thus, the first French Indian fabricators (‘indienneurs‘) were smuggler-manufacturers.

Cotton and colors

In the 18th century, Indian printed fabrics replaced silks and woolens. Easy to care for and inexpensive, they were adopted by both the working classes and the bourgeoisie.

The history of fabrics tells the story of applied arts and techniques, and also speaks to the intimate.

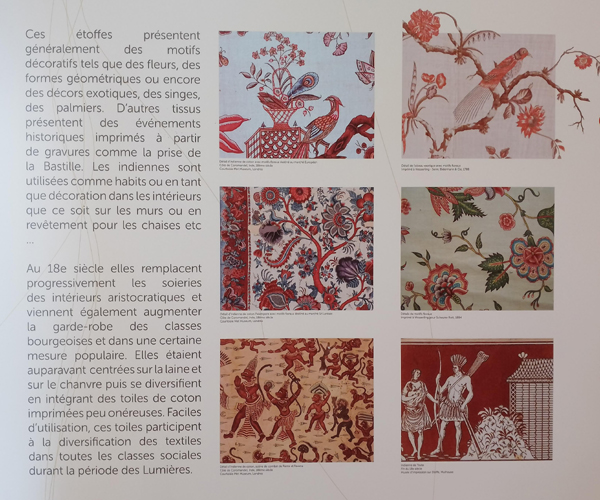

Opposite is an excerpt from a panel at the Wesserling Textile Ecomuseum.

In the rest of Europe, the importation/manufacture of calico fabrics was booming. This was particularly true in Basel, Switzerland, where Huguenot traders and artisans were exiled after being persecuted (following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685). In Mulhouse, a free city allied with the Swiss cantons, the first calico fabric factory was founded in 1746, as Alsace was not yet part of France.

Despite the ban and severe repression, the calico fashion took off. By 1759, when the ban was lifted in France, calico production was already well established throughout Europe (especially in England). It quickly developed around several industrial centers: Mulhouse, Lyon, Marseille, and the Manufacture Royale d’Oberkampf in Jouy-en-Josas, which produced the famous Toile de Jouy.

In the 19th century

The Industrial Revolution and mechanization allowed England to become a manufacturing country that directly competed with Indian production. Printing on fabrics and its artistic aspect now gave way to a textile industry that revolutionized practices. Manual processes were replaced by machines, wooden blocks and plumb boards by flat frames and copper rollers. (India mainly exported cotton, and it was in the Manchester mills that low-cost cotton fabrics were now woven and printed.)

Patterns

‘Mordançage, réserve et garançage’

The motifs of the ‘Indiennes‘ were originally drawn freehand with a stylus (calamus), a stencil (a pricked drawing reproduced by sanding), or printed with a wooden block. The coloring results from ancestral know-how, which the Europeans did not master and requires several stages. The canvas is dipped in indigo, after reserving (using wax) the parts of the drawing that should not be dyed blue. Then conversely a mordant (metallic salt) is used in the places intended for the application of madder red so that it is “fixed” on the canvas.

‘L’Indienne’: an imitation product

Indian design is above all an aesthetic, a story of patterns and drawings. The production of exported Indian printed fabrics was quickly influenced by the needs of the merchants who passed on their designs. Local Indian artists then designed decorations intended for export, adapted to European tastes. They copied European ornamentation and depicted flora they had never seen before.

In Europe, Indian fabrics were imitated by manufacturers who used their own designers. Often, flower painters were hired to paint these patterns. Indian fabrics were copied from India, then inspired by botanical works, then copied copies of Indian fabrics produced in England (because they had to keep an eye on the competition). So fabric samples toured Europe. The attraction to foreign patterns led to both cultural appropriation and industrial espionage. And that’s without taking into account the commercial and artistic exchanges from India to Persia and Asia; globalization is not new.

It doesn’t matter if the patterns of a fabric were of mixed geographical and cultural origins; the essential thing is that exoticism breathes and color vibrates. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate between fabrics designed in India for the European market and fabrics produced in Europe for a European clientele intrigued by the exoticism of oriental patterns. The fascination with a distant and fantasized world led to a global style. Yet the production of calico in each region ends up differentiating itself thanks to a style or aesthetic. For example, the light block-printed Provençal cottons are distinguished from the rich, dark cashmere fabrics of Alsace.

‘L’oeuf et la poule’

Globalization of knowledge and interdependence of industries is not new.

The history of Indian fabrics is complex and fascinating, situated at the crossroads of Art history, trade, and political history. Studying ‘Indiennes‘ means becoming aware of the exchanges between nations with the colonies, slavery, cotton cultivation, applied arts, fashion and intimate life, customs policies (!), and what we now call cultural appropriation.

What would Indian art be without Hellenistic art? Probably not quite the same. What would Greek art be without the Etruscans? (etc.) Besides, there is not just one Indian art. Art from India, but also from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, and regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan, spans several historical periods of influence.

An artist can never say that what he creates is pure or that it is free from any influence. Each gesture is the fruit of diverse impregnations and influences, of shared and personal histories, and is nourished by constraints and inventions. Each artistic gesture is a borrowing from the past and a leap toward the future. Cultural exchanges have always existed. Dealers as much as artists have been, and always will be, nomadic and curious about the production of their neighbors (and their technical innovations).

So defining the authenticity of a motif (of an art) is a complex question.

An idealized nature: extraordinary flowers, trees of life and mythical birds

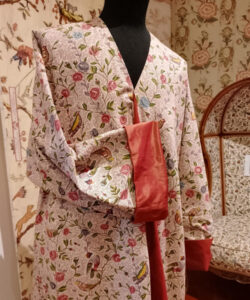

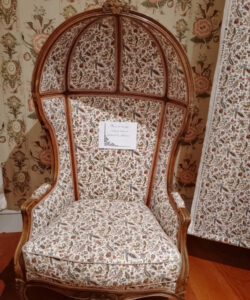

Palempores with their central motifs and floral frames became bedspreads and wall tapestries. Simple patterns were used as clothing, cashmere and palmettes adorned dresses, and complex scenes adorned armchairs. European manufacturers reinterpreted motifs that lost their original edifying and religious meaning and became decorative. The omnipresent nature was depicted idealized, the flowers were extraordinary, and the birds were mythical.

Patterns vary according to tastes and uses, as well as techniques. In 1797, the Oberkampf factory used the first copper roller printing machine. The size of the roller patterns decreased, and they were framed with “ornate backgrounds” to hide the repetition. Mechanization then spread to England and soon to all of Europe. The artisanal aspect of the fabrics gradually disappeared with mechanization.

While indigo and madder dominated the palette, the Indians became increasingly colorful (up to fourteen colors). Toile de Jouy, for its part, offered finely drawn and monochrome genre scenes, thanks to the improvement of printing techniques (copper plate and roller).

Patterns that reflect the French ‘Art de vivre’

At the Wesserling Castle we are greeted at the beginning of the exhibition by panels of reissued fabrics, a housedress and an upholstered armchair, which seem familiar to us as these motifs have entered the collective memory.

Coquecigrues (meaning absurd, burlesque), the successful motif of the Oberkampf factory (1792), represents fantastic animals, half insects, half birds, and imaginary flowers.

The famous Ananas motif, reissued by Maison Pierre Frey (2023) for the Queen’s private apartments at Versailles, is part of the Braquenié X Frey anniversary collection, in collaboration with the Musée de la Toile de Jouy. It is one of those classic and timeless motifs that seem emblematic of a certain French Art de vivre.

The time of Indian printed fabrics

Indian printed fabrics are still present in our homes and wardrobes. Fine block-printed cottons and paisley patterns were revived in the 1960s by a youth enamored with orientalism. Today’s bohemian brands are following suit, even if most of these prints are now designed on tablets or graphic palettes, as blocks have been replaced by digital textile printers.

Maximalist floral patterns are more trendy than ever in the world of decoration. Major fabric designers have their own catalogs of heritage patterns. As we’ve seen, they’re reissuing their most beautiful patterns in fabrics or wallpaper in settings that capitalize on a taste for a certain classicism and nostalgia, in search of authenticity and a (supposed) past grandeur?

One thing is certain: Indian women are at the origin of an aesthetic vocabulary still used today. Libraries of Indian patterns are literally plundered by contemporary designers.

Le parc de Wesserling

The Wesserling Textile Printing Factory was founded in 1762. The Wesserling industrial site then expanded, reaching its peak in the 1960s. The block printing building dating from 1819 has since been transformed into a textile ecomuseum, whose mission is to showcase Indian printing techniques and also document the lives of the valley’s workers. Its remarkable castle and gardens make it an ideal destination, between Art and Nature, for lovers of History and fabrics.

A visit to Wesserling Park is ideal during the summer season to enjoy the gardens.

Ressources & liens

- Le Parc de Wesserling : https://www.parc-wesserling.fr/

- Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes de Mulhouse [Site du Musée]

- Musée de la Toile de Jouy [Site du Musée]

- Tissus CASAL : https://www.casal.fr/an/history/textile-origins.html

- Archives des tissus Oberkampf (Casal): [Flipbook Patrimoine]

- La Maison Antoinette Poisson (du vrai nom de Mme de Pompadour amatrice d’indiennes) s’est spécialisée dans la réédition de pièces du patrimoine

- La bible des ouvrages consacrés aux tissus: The Book of Printed Fabrics, Taschen, 900 échantillons de tissus originaires de quatre continents, issus des collections du Musée de l’Impression sur Étoffes de Mulhouse.

Voici la liste des documents (passionnants) qui m’ont aidés à la rédaction de cet article, et dont j’encourage la lecture si vous souhaitez en savoir plus:

- Indiennes sublimes https://villa-rosemaine.com/sites/default/files/catalogue/VillaRosemaine_IndiennesSublimes.pdf

- Le textile, un objet interculturel ? Processus de valorisation et d’appropriation des modèles étrangers dans les toiles peintes (XVIIIe-XIXe siècle) par Aziza Gril-Mariotte [document]

- Commerce et contrebande des indiennes en Provence dans la deuxième moitié du XVIIIe siècle. [article]

- Négoce et industrie à Mulhouse au XVIIIe siècle (1696-1798) Isabelle Bernier [Chapitre 1: La naissance de l’indiennage à Mulhouse]

- L’indiennage en Suisse [article]

Crédits photos © Andrea Leonelli 2025 prises à l’écomusée de Wesserling (sauf mentions contraires)